INTO THE ROQUEFORT CHEESE CAVES

CHEESE, GLORIOUS CHEESE!

For those who appreciate dairy products, there is one variety of cheese that brings out strong opinions, both for and against: Roquefort. Whether you love it or hate it, the creamy, ivory-coloured cheese with blue-green veins and a distinctive pungent odor is famous around the globe. Some even call it the King of Cheeses.

We went out of our way in southern France to visit the renowned caves where this cheese is produced, to the sleepy hamlet of Rouquefort-sur-Soulzon in the Aveyron region. Bruce had visited the caves as a child and looked forward to a return. There are a few “fromageries” in the cave system, but we elected to visit the most well-established: the Roquefort Société cellars, where 60% of the world’s Roquefort cheese is aged. This cave system has been used to produce Roquefort since 900 C.E., while there is archeological evidence of cheese being produced in the area as far back as 2000 B.C.E. Having been at it for so long, they must know what they’re doing by now.

WHERE IS IT?

The famous caves are reached by turning west off the A75 highway, just south of the spectacular Millau Viaduct, which is the world’s tallest bridge (more on that later). After less than 20 kilometres of winding through green hilly farmland, the road reaches Roquefort-sur-Soulzon. The Société Fromagerie is located at the top of the village, with the parking lot easy to find.

THEY EVEN HAVE THEIR OWN RESTAURANT

There are tours throughout the day and while waiting for our tour we enjoyed a delicious lunch in their restaurant, La Cave des Saveurs (“The Cellar of Flavours”). It is located right beside the car park, in a cave (of course), but with some outdoor tables to take advantage of the expansive view. Most of the food came with a light and tasty Roquefort sauce, as expected.

OUR CAVE TOUR

The tours run year-round, but take note that the ripening of their cheese takes place from January to July, so you will not see cheese production in the Société Caves outside this period. We were there only a few days into July, so the only production we saw was on film, but there were plenty of cheese wheels still ripening in the large caves. Also, tours are run in French, but we were given an English information sheet to follow along with and our guide was happy to answer any questions in English.

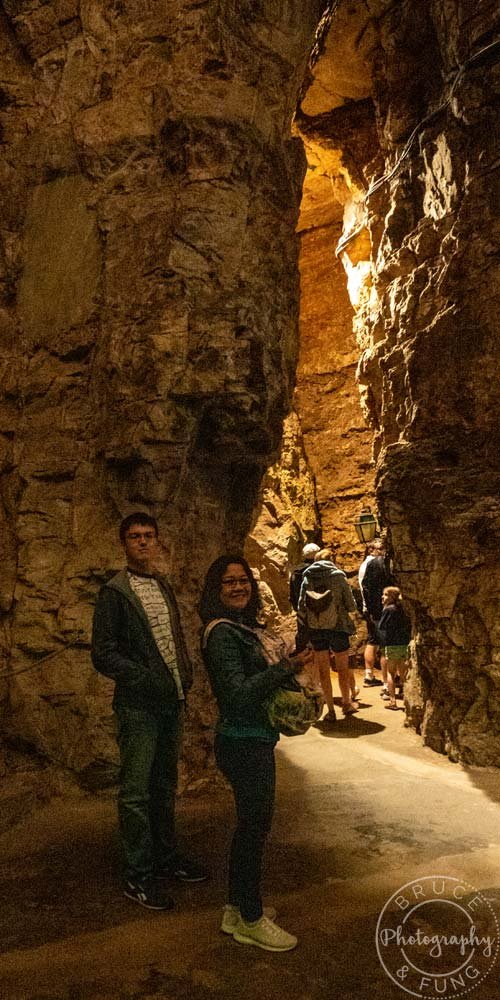

The one-hour tour began with a 3D film showing how the Société caves were formed. Then we descended further into the 12,000m² of multi-levelled caves and learned about the natural venting system that allows the cheese-makers to control the flow and temperature of air reaching into the caves from outside. Fissures known as “fleurines” are small tunnels that channel breezes through the partially-collapsed mountain. Vents were added to control the flow by allowing more or less air into the caves. Different caves had slightly different temperatures, which meant that the ripening of the cheeses and development of flavours could be altered depending on which caves were used in the process.

The temperature in the caves is around 10˚C, which meant that we brought warmer clothing, as recommended. But we saw others in our tour group unbothered by the cold, including small children merrily skipping along in shorts and t-shirts. When we visited, the outside temperature was around 40˚C, so the difference was quite noticeable.

Then we watched a second short film, this time showing the production stages of how the cheese is created. It starts with milking the local Lacaune sheep and takes the viewer through the processing of this milk into the finished product.

In “the old days”, the process followed the traditional French cheese-making methodology of this area. The cheese-maker would leave a local loaf of sourdough bread, teeming with starter cultures, in the underground caves, which are already naturally rich with the spontaneously flourishing Penicillium Roqueforti. He would allow the bread get moldy, then grind up the moldy loaf and mix the breadcrumbs with goat milk curd. The cheese would then be left to age in the caves where the bread went moldy, which encouraged the development of blue veins.

That was the old school method. Now most cheese-makers use a Penicillium Roqueforti that is made in labs because it results in more consistent blue-green veining. Also, each Roquefort cheese-maker cultivates their own individual strains of Penicilium Roqueforti.

Following through a number of caves, both spacious and narrow, we eventually came to a number of large caves fitted with long tables. These rooms are dedicated to the ripening of the Roquefort cheese wheels under the watchful eye of their “Master Affineur” (“Cheese Ripener”, which surely must be a highly prestigious entry for any CV).

At the end of our tour we got to taste all three Roquefort AOP Société cheeses, laid out in bite-sized morsels for our sampling pleasure. The weakest of three hit the spot for all of us. But we found that the two stronger varieties were just too eye-watering and throat-burningly intense for our taste buds.

OUR VERDICT: WELL WORTH IT

Overall, we really enjoyed this fascinating outing into the cool caves of Roquefort. The tour was a learning experience and heightened our respect for this distinctive cheese. Since that day, whenever we eat roquefort cheese, our minds are immediately brought back to memories of our afternoon in, around and under Roquefort-sur-Soulzon.

TOUR INFORMATION

- All Société Tours are guided (duration: 1 hour)

- Adults : 7€, Children : 4€, but free up to the age of 6

- The tour schedule can change at different times of the year, so check ahead to avoid disappointment.

- For more information: https://www.roquefort-societe.com/les-caves/

The Millau Viaduct

While in the area, the spectacular Millau Viaduct is well worth a visit. It is the tallest bridge on Earth, though the claim is based on the height of the towers, which are taller than the Eiffel Tower, rather than the height of the bridge deck itself (277 meters), which is only the 17th tallest in the world. Completed in 2004 to span the Tarn River Valley, it is a striking and stylish feat of engineering.

We drove from Roquefort-sur-Soulzon on back roads, ending up beneath it. Once underneath it took quite some time, meandering through the town of Millau, to actually reach the bridge. From this journey we realized how much time the toll bridge saves compared to the winding, older, existing roads, which is 45 minutes to 3 hours, depending on traffic. At the north end of the bridge there is an exit to a rest stop which offers food and views of the viaduct.